-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

Fiddling “In the Barn” with Charles Ives

Monday, August 3, 2020

Posted By:Dr. Jacob A. Cohen, Visiting Assistant Professor in Musicology, Oberlin Conservatory

—

Charles Ives loved a good, old-fashioned, rural barn dance. At least, he thought he did. Ives readily admits that his musical representations of the barn dance—as heard in pieces like “Washington’s Birthday” from the New England Holidays Symphony, or the finale of his Second Symphony where Ives refers to old fiddle tunes as “barn-dance fiddles”—comes from a combination of his own remembrances “of these dances as a boy, and also from father’s description of some of the old dancing and fiddle playing.” Rather than memorializing a specific memory, Ives’s barn dance likely signifies an idealized event, one that he constructed from a combination of family anecdotes, childhood memories, and fabrications based on his conception of a mythological “Old Danbury.”

“In the Barn,” the second movement of the Second Violin Sonata, delivers this idealized country dance primarily through its quotation of tunes that would have been part of the repertoire of a country dance band in late-nineteenth-century New England. These include old time contra dance fiddle tunes, as well as more modern, popular melodies like the minstrel song “Turkey in the Straw” or the Civil War era hit “Battle Cry of Freedom.” However, even more important than the tunes that Ives quotes is the attitude with which the violinist and pianist play them.

Scratch that...the fiddler and the pianist. Ives’s goal with his barn dance music was to reflect the “backwoods fun and comedy and conviviality” that was “gradually being forgotten.” To do this, he wanted his players to sound like amateurs, like the fiddlers who might have been “seated too near the hard cider barrel.” A prime example of this is the original fiddle tune melody that begins “In The Barn.” Ives writes a quadrille-style melody but adds in an extra beat, so that the piano and violin go out of sync. The effect is not only modern (foreshadowing Stravinsky’s later neoclassicism), but also wonderfully evocative of what happens when the “backwoods fun” gets a little too convivial. These rhythmic irregularities, melodic interruptions, and dissonant “mistakes” permeate all of Ives’s barn dance music.

Beyond this, Ives wanted to be sure that his barn dance violins sounded like fiddles, and not violins. Speaking about the violins during the barn dance section of “Washington’s Birthday,” Ives told conductor Nicolas Slonimsky to “let em ‘git it going’—no pretty tones and long bowing.” For a recording of that piece, Ives advised the session manager that “it’s a rough dance and the strings should fiddle it and not ‘play it too nice’ on the accents.” And for a performance of the Second Violin Sonata in the 1940s, pianist John Kirkpatrick wrote to Ives with enthusiasm about collaborating with a country fiddler named Louise Rood, who “knows a lot about country fiddling.” It’s fun to imagine the violinist playing this sonata, a genre that carries immense cultural capital, with her fiddle against her chest, rather than under the chin, scooping into notes in a way that would make most conservatory violinists cringe.

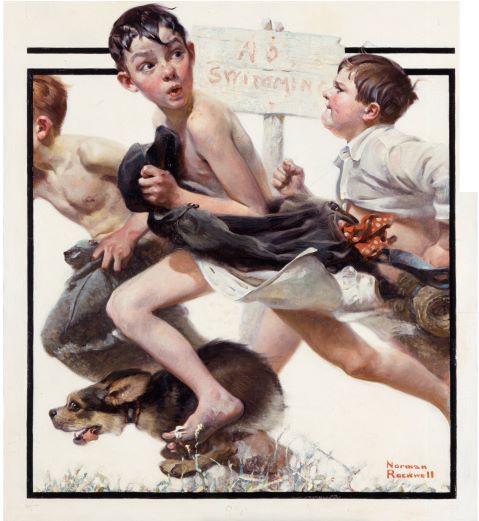

No Swimming, 1921 (oil on canvas) by Norman Rockwell. Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, June 4, 1921. From the collection of Norman Rockwell Museum. © 1921 SEPS: Curtis Licensing, Indianapolis, IN. All rights reserved

For Ives, the purpose of these musical evocations of the barn dance was to construct, and even fetishize, an imagined, antebellum “Old Danbury.” But country dance movements like “In The Barn” also allowed writers and critics, and ultimately audiences, to frame Ives within an emergent New England identity, one that erased racial and ethnic difference in favor of white, rural, Protestant homogeneity. Since the late nineteenth century, representations of New England in art and literature were increasingly located in this white, rural, small-town village identity: think Sarah Orne Jewett’s novel Deephaven, or populist Depression-era works such as the illustrations of Norman Rockwell or Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Even Ives’s evocation of ragtime, which he does in the piano part of “In The Barn,” could by midcentury be heard as “American” rather than “Black.” Thus, the barn dance helped to cement Ives’s music, and his “Old Danbury,” as belonging to that imagined rural New England.

[1] Charles E. Ives, Memos, ed. John Kirkpatrick (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), 52, 97.

[2] Ibid., 97.

[3] Letter from Ives to Nicolas Slonimsky, August 1931, and letter from Ives to Wallingford Riegger, 13 May 1934, both contained in the Charles Ives Papers in the Irving S. Gilmore Music Library of Yale University.

[4] Letter from John Kirkpatrick to Ives, 31 August 1944, contained in the Charles Ives Papers.

Dr. Jacob A. Cohen is a musicologist specializing in American classical music of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as American rock music from the 1960s–present. His work examines how composers such as George Chadwick, Edward MacDowell, Charles Ives, and Carl Ruggles used myths and narratives of New England identity to reflect and articulate their sense of place. He has also presented papers and published essays on rock bands such as Talking Heads, the Grateful Dead, and Phish. Dr. Cohen is currently Visiting Assistant Professor in Musicology at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music, and has previously taught music history at colleges in New York, New Jersey, and Washington. He has presented his work at national and international conferences, and given invited talks at universities around the U.S. He lives in Greenfield, Massachusetts, with his wife Rose and their dog, Coconut. For more information and a full list of activities, visit his website at https://musicolojake.com.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03