-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

Withdrawn from “the diversions of society”: Seclusion and Beethoven’s Chamber Music

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

Posted By:Dr. Sarah Clemmens Waltz, Associate Professor, University of the Pacific

—

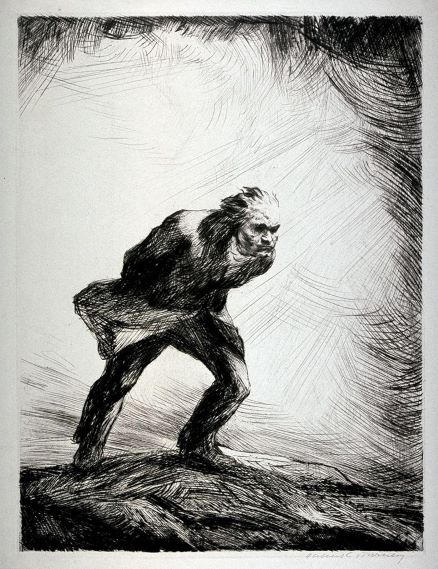

Beethoven on the Mountain, 1922 (drypoint) by Julius C. Turner. San Francisco Museum of Art/Achenbach Foundation for the Graphic Arts

What is chamber music for? Unlike our modern experience of music, it was the way most music was made in Beethoven’s time. Indeed, chamber music was often for making more than for listening: a sort of musical socializing in which musicians experienced music together and communicated to each other through the music that privileged witnesses could also hear. It can be surprising to realize that, in Beethoven’s time, even virtuosic piano works like the Hammerklavier Sonata (probably, in 1818, the most difficult piano work to that date) were meant for the gratification of the player and a private circle, with no public platform such as a piano recital to emerge until some years after Beethoven’s death. “Private” performances, however, might still impress a number of important listeners, such as if the work were played in an aristocratic home or salon.

Beethoven, as a pianist, probably imagined himself performing the piano role of any music involving the instrument, but his own performances declined as his deafness increased. His final public performance in early 1815 was the last gasp of what had once been the career of a performing virtuoso pianist. Beethoven’s deafness, which he realized was incurable around 1802, became profound by 1816–17; to that and to his mercurial gastrointestinal illness he attributed his increasing isolation from others.

Although we have often conceived of Beethoven’s middle and late years as a battle with deafness and illness, it is his battle with isolation which is perhaps most moving and with which we can all identify today. Beethoven’s need for human connection and simultaneous inability to fully achieve it—common to the human condition—is visible in almost every aspect of his biography: his family relationships, his fraught interactions with his teacher Haydn, his alternation between relying on patrons and fierce independence from them, his conflicts concerning his unmarried state, and of course the cri du coeur in the 1802 Heiligenstadt Testament—essentially a will in which Beethoven reveals the heartbreaking tension between his desire for companionship and need to avoid it:

Though born with a fiery, lively temperament, susceptible to the diversions of society, I soon had to withdraw myself, to spend my life alone. And if I wished at times to ignore all this, oh how harshly was I pushed back by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing; and yet it was impossible for me to say to people, ‘Speak louder, shout, for I am deaf.’

[F]or me there can be no relaxation in human company, no refined conversations, no mutual outpourings. I must live quite alone, like an outcast; I can enter society practically only as much as real necessity demands. (translated by Barry Cooper)

Beethoven notes that period of uncertainty around his hearing stretches back six years to 1796, and thus includes many of his early-period works: the first 8 violin sonatas (such as the Op. 12 set and the popular “Spring” Sonata Op. 24), the Op. 18 string quartets, many wind chamber works, and piano sonatas such as the Op. 27 no. 2 Sonata quasi una fantasia, known as the “Moonlight” Sonata.

Beethoven’s enduring popularity is partly because listeners and performers relate to what they find to be expressed through his music. Beethoven himself claimed that he often had a “poetic idea” behind his works and sometimes complained that listeners were less perceptive than they had once been. Whatever he intended to communicate, it is certain that the most enduring popularity has attached to works that conveyed some poetic idea via a title, even if that title was not given by Beethoven. “Spring” Sonata and “Moonlight” Sonata are titles inspired by the reception of listeners, rather than given by the composer, although stylistic hallmarks (such as from the “pastoral” or “nocturne/moonlight” styles respectively) are present in the music to support listeners’ ideas.

Though Beethoven may not have intended to express it, today we cannot help but to identify with his isolation, and perhaps even with the dark thoughts that led him to write a will. It is worth remembering that he also wrote in that document:

Such incidents brought me almost to despair; a little more and I would have ended my life. Only my art held me back. Ah, it seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt was within me[.]

Thus Beethoven’s answer to isolation was to continue to communicate with the art he made, until he could make it no more.

Sarah Clemmens Waltz holds both a BA in physics from Oberlin College and a BM in musicology from Oberlin Conservatory, where she also studied flute with Michel Debost and Kathleen Chastain. She received her PhD in Music History from Yale University in May 2007. Her dissertation, The Highland Muse in Romantic German Music, concerns the image of Scotland in late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century German composition and criticism.

Dr. Waltz has published Beethoven-related articles in Beethoven Forum and the Beethoven Journal; an essay is forthcoming in the volume Music and the Idea of the North. Current projects include editions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century lieder based on Scottish and imitation Celtic poetry (A-R Editions) and a book on Scotland's importance to German romanticism.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03