-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

“Some miserere modern enough”: Auden, Bernstein, and The Age of Anxiety

Thursday, July 10, 2025

Posted By:Imani Mosley

—

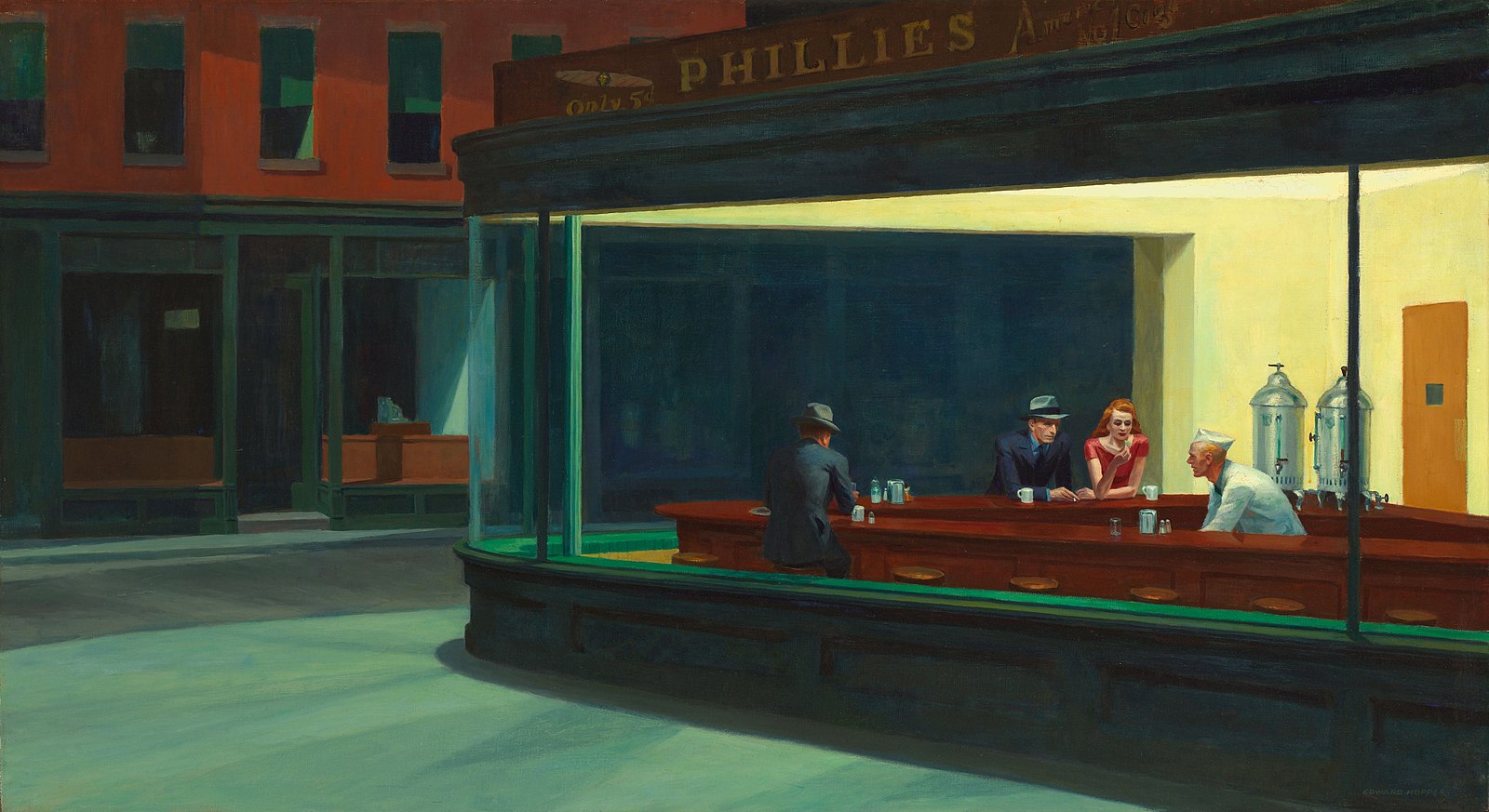

Nighthawks, 1942 (oil on canvas) by Edward Hopper. Wikimedia Commons/The Art Institute of Chicago.

W. H. Auden’s The Age of Anxiety is, in some small part, a repudiation and reclamation of “September 1, 1939,” a poem he believed to be his “most dishonest” despite its cultural impact as a reflection on the arrival of fascism and authoritarianism. In “September 1, 1939,” meaning is clear: “We must love one another or die.” In Age, wartime has changed us, left us “reduced to the anxious status of a shady character.” This is how we are introduced to the four characters in the poem—Malin, Quant, Emble, and Rosetta—who encapsulate the temporal and emotional distance of this poem through their conflicts. In a lecture to Oxford students, Auden highlighted this distance:

The war is in the dreadful background of the thoughts of us all, and it is difficult indeed to think of anything except the agony and death going on a few thousand miles to the east and west of this hall […] the overwhelming desire to do something this minute to stop it makes it hard to sit still and think.

Auden was often concerned with structures of time in his work, and we see this in Age: while the poem takes place during wartime, the shared dream of the four characters seems unbound by war even as a nameless voice booms news and advertisments through the radio, punctuating this journey with the dreary, quotidian affairs of the distant campaign. The characters, being apart from this catastrophe, must continue living while being both in and out of time. Time flies? No, Time returns.

This way of approaching anxiety, as this time-bound thing waiting to be filled with something while simultaneously being taken up with the banality of living, feels different from the explicit anxiety of the postwar period. If anything, time moved too fast in those days, hurtling on towards an unknown event. Postwar anxiety is the Doomsday Clock, supersonic speed, suburban sprawl, the end of history. A term coined by political scientist Francis Fukuyama in 1989, the end of history signifies a teleological worldview in which neoliberal democratic governance is understood as mankind’s ideological apogee; it was a state made possible only after the conclusion of the Cold War. The end of history, in other words, would come about through the defeat of fascism and communism.This is the anxiety of Bernstein’s two-part Second Symphony: the sense that society is rushing toward its end. And while both works were written after the end of World War II and meant to take place during the war, Bernstein’s work also seems to elicit the question of what comes next.

Bernstein envisions Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942, above) as the setting for the opening part of Age. This famous painting depicts four lonely people who never touch and never look in the same direction. In an interview with Humphrey Burton, Bernstein recalls Nighthawks as the mood of the Symphony’s opening, in part because of its visual analogue to both his symphony and Auden’s poem—three men and one woman in a restaurant or bar late at night—and in part because of how it frames Bernstein’s understanding of anxiety. The anxious bar sets up the “forced hilarity” of the later jazz scene that we hear in the second part, Masque, where those lonely people are desperate to find connection.

Bernstein’s Anxiety is pointedly American: it is a new feeling and a new art for a new world. The somewhat improvisatory feel that runs throughout the work emphasizes this novelty, as does the Symphony’s focus on developing a palpable sonic architecture in place of traditional symphonic form. It feels rooted in American art’s postwar desire of capturing and depicting feeling itself rather than conveying meaning. Abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock represented an artform seemingly divorced from the European styles that had been corrupted by authoritarianism and war, and embodying instead American success, fear, masculinity, speed, growth, and of course anxiety.

Bernstein’s long history with popular American musics makes the jazzy sound of the Masque in theory unsurprising. But its occurrence here speaks less to Bernstein’s comfort with the sound (though this was the first section of the symphony he wrote, and under far more relaxed conditions than the rest of the work) and more to this new postwar necessity of feeling. The jazz of the Masque is just as hollow as the other sonic representations in the piece: of fanfare, concerto virtuosity, and symphonic form. The music throughout Age does its best to be feeling without meaning, a programmatic work devoid of a program.

In 2018 the New Yorker noted that Francis Fukuyama was postponing his prediction of the end of history. This rescinding of his prediction mirrors something within Auden’s poem. The characters navigate their own individuality (or lack thereof) via highly stylized poetic language and form. Their difficulty in placing themselves both in and out of time highlights the tenuous nature of wartime anxiety. Bernstein’s play with form and style similarly highlights this quality of feeling both rooted and unsettled, familiar and distant. Thus do Auden and Bernstein’s postwar anxieties linger: “On our present purpose the past weighs / Heavy as alps.”

You can hear James Conlon conduct piano soloist Inon Barnatan and the Aspen Festival Orchestra in Bernstein’s The Age of Anxiety on Sunday, July 13 at 4:30 pm in the Klein Music Tent.

Imani Danielle Mosley is assistant professor of musicology and affiliate assistant professor in the Center for European Studies at the University of Florida. Her research focuses on Benjamin Britten, opera, and modernism in postwar Britain. Her current research addresses sacred sonic culture, acoustics, and ritual in the English churches central to Britten’s sacred music. She has published articles in The New York Times on British royal ceremonial music and also specializes in reception history; masculinity studies and queer studies; digital humanities and artificial intelligence; sound studies; and race, protest music, and trauma.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03