-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

“The Eternal Beginner”: Repeating Mahler ’s Fourth Symphony

Friday, August 8, 2025

Posted By:Erin Pratt

—

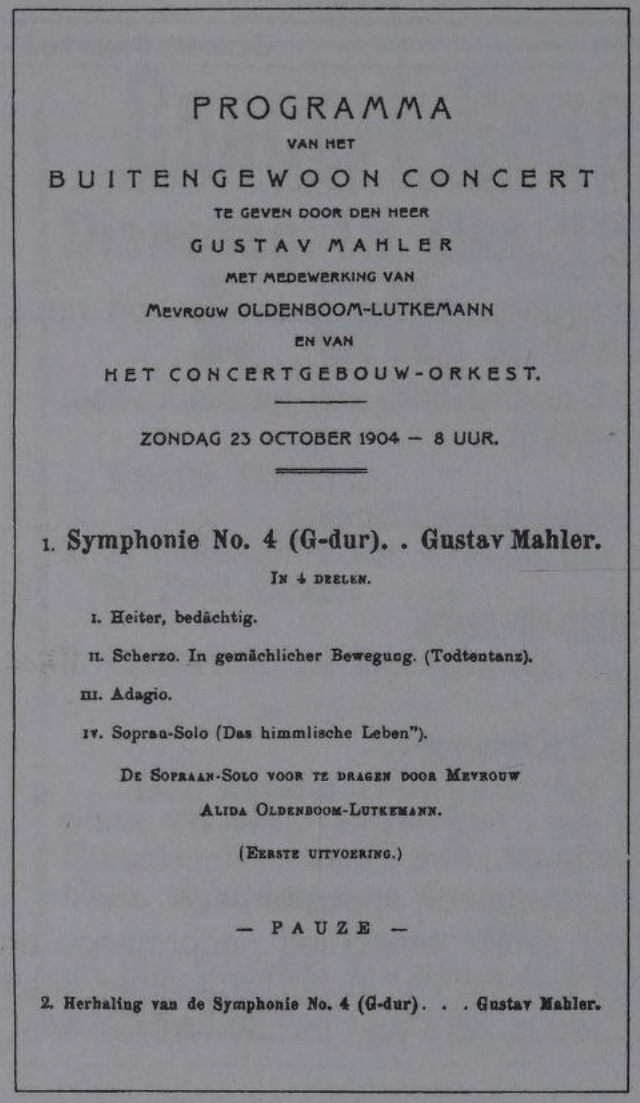

A program for the Amsterdam premiere of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony on, October 23, 1904; reproduced from Knud Martner, Mahler’s Concerts (Kaplan Foundation, 2010), in which this item appears as no. 166, p. 188.

Let us begin in the middle.

Mahler conducted the Amsterdam premiere of his Fourth Symphony on October 23, 1904, after three years of a largely hostile reception to the work. Mahler immediately went on to conduct the second Amsterdam performance of the Fourth directly after the intermission; the program page for the concert, reproduced above, describes the second half of the concert simply as a “repetition of the Symphony No. 4 (G major).”

Repetition has a bad reputation. “Repetitive” is often used as a pejorative; we think of variety and novelty as virtues in a composition. But classical music centers on repetition on both micro and macro levels. Mahler’s Fourth illustrates this well. The opening motive, with its famous sleigh-bells, repeats itself throughout the Symphony, most prominently in the first movement’s recapitulation. The third movement is built around the theme and variations form, which derives its power from repetitions on the levels of surface and structure both.

Beyond the features of any individual piece, though, is the fact that the classical tradition itself relies upon repetition. Musicians repeat themselves in practice, in rehearsal, in performance; composers iterate on the forms, genres, and themes of the past. Repetition is a sign of love, of respect, of hope: it expresses faith not only in the value of that which is repeated, but also in constant improvement through iteration, variation, and development.

Mahler’s twin performances of the Fourth celebrate this aspect of repetition. By programming his troubled Symphony twice on a single concert, he put his faith in the music to endure the redoubled scrutiny of the audience, and in the audience to recognize the depth of the piece. And to his mind, at least, the gamble paid off. “That was an astonishing evening!” he wrote in a letter to his wife. “The audience was so attentive and understanding from the first, and became warmer from movement to movement. — The second time the excitement grew. . . . It was an image painted on gold.”

For Mahler, repetition had a spiritual dimension. He embraced what Gilles Deleuze would later call “repetition for itself,” which recognizes that no two repetitions are (or ever could be) actually identical. This outlook enables one to observe the difference that exists within repetition and between repetitions. Mahler wrote in 1900, as he was in the thick of finishing the Fourth, that it “is so fundamentally different from my other symphonies. But that must be; it would be impossible for me to repeat a state of being—and as life goes on, thus I traverse in each new work new pathways. . . . Thus one remains eternally a beginner!” This figure of the “eternal beginner,” who emerges frequently in Mahler’s writings, echoes the Nietzschean concept of eternal recurrence, the ever-changing but inevitable return. As the philosopher Catherine Pickstock has written, if something “can only be varied by being repeated . . . then inversely it can only be repeated by being varied, by becoming other from itself.”

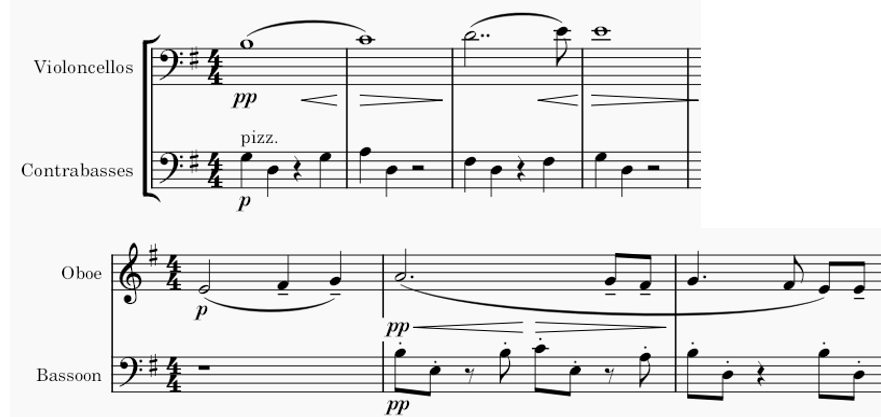

The third movement of the Fourth Symphony—in many ways the heart of the entire piece—plays with this tension between repetition and variation, development and cyclical motion. Like the slow movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (performed earlier this season by the Aspen Chamber Symphony), the slow movement of Mahler’s Fourth is a double variation movement, treating two distinct themes. The first, in a consonant G major, is recognizable in its repetitions primarily through key and timbre; as a melody, it goes everywhere and nowhere, never establishing a truly identifiable motive. The second theme contrasts profoundly with the first: it begins in E minor, it exhibits a distinct melodic line, it is unsettled by recurring accented dissonances, it is introduced by the winds rather than the strings. And yet despite these distinctions, the sections share one important feature: their bassline. What initially seem to be two separate themes are, at a basic level, repetitions of each other—opposing variations that share a single foundation.

Above: Mahler Symphony No. 4, Third Movement, mm. 1–4, first cello and bass only.

Below: Mahler Symphony No. 4, Third Movement, mm. 62–4, oboe and bassoon only.

Over the course of the ensuing variations, the apparently separate themes intermingle, each occurrence of one theme drifting away from repeating itself and beginning to repeat its other. Each moment is different, despite the impression of sameness and unity suggested by the form and the repetition of the bassline. The interpenetration of these themes ultimately destabilizes the structure of the movement, as it is continually interrupted by interjections from outside the closed loop of the variation form.

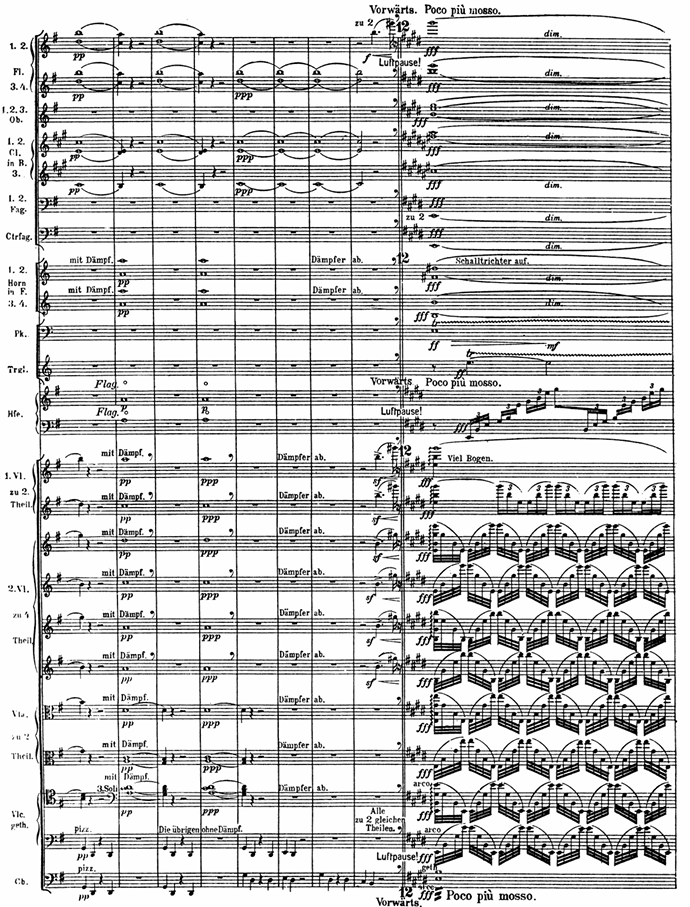

The last of these interruptions, a massive triple-forte breakthrough in E major, makes as much of an impression on the reader’s eye as it does on the listener’s ear:

Mahler Symphony No. 4, Third Movement, mm. 307–315.

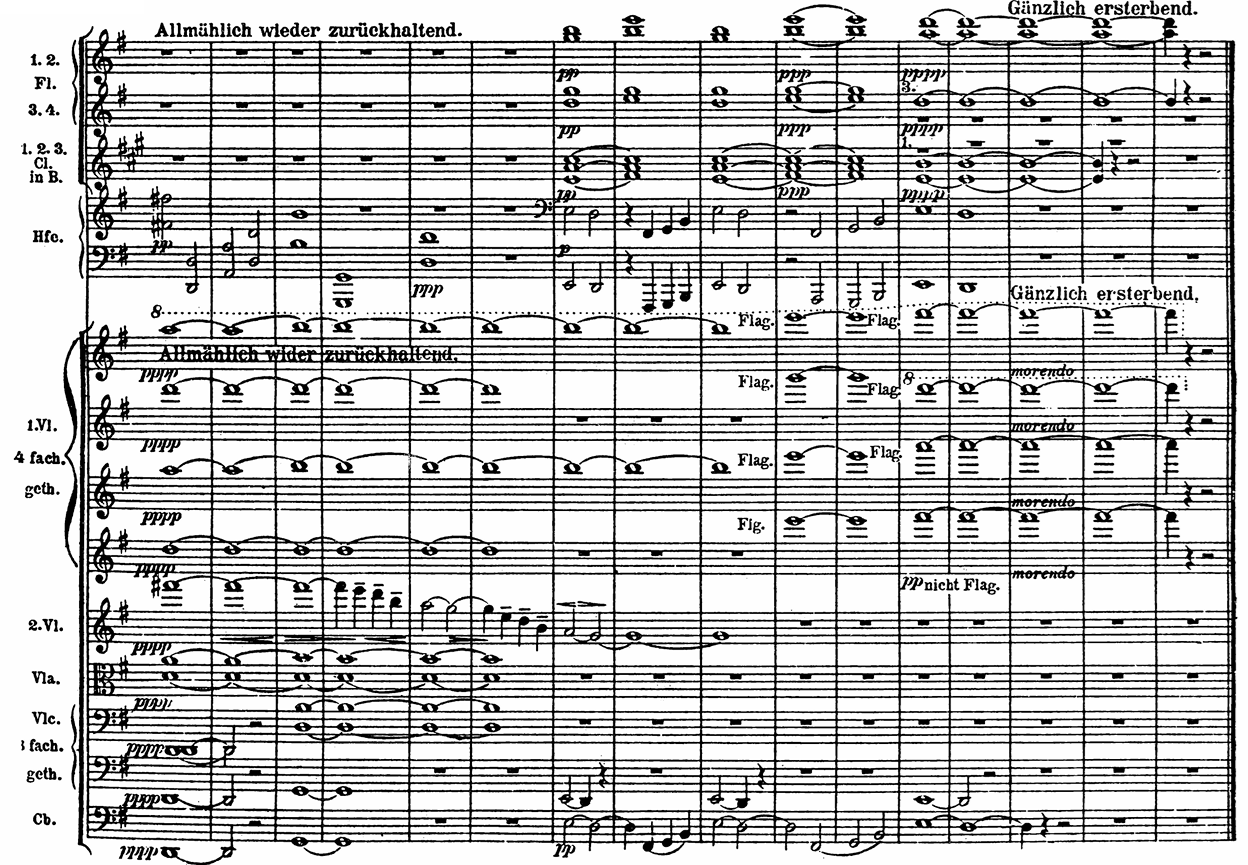

Here, at the end of the third movement, a new combination of repetitions—the apotheosis of a theme first heard in the development of the first movement, pronounced over a final iteration of the third movement’s bassline—disrupts the course of the music so thoroughly that the variation form, which defines itself through its ability to repeatedly achieve a cadence in its home key, ends instead on its own dominant, a D-major triad.

Mahler Symphony No. 4, Third Movement, mm. 338–353.

Thus the “eternal beginner” has used the difference within repetition to offer a new beginning, a pathway towards the heavenly mystery of the final movement. And then, after bringing the symphony to a close, he picks up his baton and does it all again.

You can hear the Aspen Conducting Academy Orchestra and mezzo-soprano Tivoli Treloar perform Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with conductors Ricardo Ferro, Tengku Irfan, Heidi Cahyadi, and Mariano García Valladares at the Klein Music Tent on Wednesday, August 20 at 5 pm. This final ACA concert of the summer will also see our students honored with the conferment of the conducting prizes. All of the concerto competition winners who performed with the ACA Orchestra this summer will also be honored during the event.

Erin Pratt is a musicologist specializing in German-language vocal music from Luther to the present. She completed her PhD in musicology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she studied with Naomi André and Mark Evan Bonds. Her dissertation, Freedom and Repetition in German Strophic Song, argues for the positive aesthetic value of repetition in classical music, with a particular focus on the long-derided strophic song form. She has served as the assistant program book editor for the Aspen Music Festival and School this summer.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03