-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

Between the Sacred and the Symphonic: Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony

Thursday, July 3, 2025

Posted By:Peter Mercer-Taylor

—

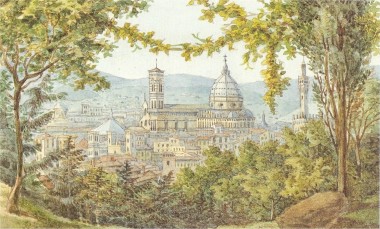

View of Florence, 1830 (watercolor) by Felix Mendelssohn. Wikimedia Commons. Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony was completed shortly before he began the tour of Europe that took him to Italy, where churches like this one in Florence were home to a famous Catholic style of polyphony. The Symphony opens with an invocation of this music.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847) would probably have been astonished, perhaps discomfited, at the amount of ink scholars would ultimately spill over the matter of his Jewish identity. The Mendelssohns were certainly conspicuous among German Jewry; Felix’s grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn, was the eighteenth century’s most celebrated Jewish intellectual. But Felix’s household was not observant, and he was seven years old when, with his three siblings, he was baptized into Protestant Christianity. He bore his heritage proudly, and his life was touched by antisemitism, his legacy even more so. But Mendelssohn lived his post-baptism life a Christian. Indeed, Christian works—chorale cantatas, service music, his oratorio St. Paul, and beyond—factor more significantly in his output than in that of any major contemporary.

While Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony demands viewing through a Christian lens, just how it fits among his Christian works (if it can even be considered one) is a provocative question. It has never achieved the popularity of Mendelssohn’s Italian and Scottish Symphonies, but is probably the most conceptually ambitious of the three, not least in the novel way it straddles the symphonic and the sacred.

The Reformation Symphony brought considerable frustration to its composer. Mendelssohn conceived it as an occasional piece for Berlin’s celebration of the 300th anniversary of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession to Emperor Charles V (June 25, 1530), a major milestone in the crystallization of Lutheran Protestantism. This appears to have been wishful thinking on Mendelssohn’s part; there’s no evidence of even an informal commission. By the time of the Symphony’s belated completion on May 12, preparations for Berlin’s June celebration were well underway. Mendelssohn’s Symphony wasn’t heard. Efforts at 1830 performances in Leipzig, Munich, and Paris having failed, Mendelssohn finally conducted the Symphony’s premiere in Berlin on November 15, 1832. He never performed it again, nor published it; he wrote to his friend Julius Rietz in 1838 “I can hardly stand the Reformation Symphony anymore and would rather burn it than any other piece of mine.”

It’s lucky he didn’t. The Reformation Symphony is a remarkable piece, if a rather strange one. It is a work that speaks quite differently when viewed on the one hand as the occasional piece it was meant to be, or on the other as a bold contribution to the symphonic genre at large, which in Beethoven’s wake was presumed to aspire to timeless significance.

As an occasional work, the Symphony is frankly programmatic, anchored in storytelling. The first movement’s slow introduction opens in a Catholic world, with Palestrina-like imitative polyphony giving way to the distinctive five-note ascent of the “Dresden Amen,” which was composed in the 1770s for Dresden’s Catholic court and would later appear in Wagner’s Parsifal. Midway through this introduction, however, the voice of the Reformer intrudes: a gathering series of hortatory blasts from brass and woodwinds that sets the tone for the stern, slightly unctuous Allegro con fuoco. Reformation is at hand.

While the middle movements—the rollicking crowd-pleaser of a Scherzo, the pathos-laden arioso slow movement—appear not to advance this narrative, the final movement reveals Luther’s work coming to fruition. The finale opens with Luther’s own chorale Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott intoned by a solo flute that the orchestra gradually accumulates around. Reengagements with the chorale, which recurs in various guises, punctuate the triumphant Allegro vivace that follows. Luther’s final phrase brings the Symphony to a full-throated close.

When viewed in this way, the Symphony contains sacred music without being sacred music. Assorted musics of Christian worship are invoked, but to symbolic ends, as characters in a historical drama. When we pivot to the question of posterity, however—of the Symphony’s enduring artistic significance—that historical drama itself retreats from view. For beneath this Symphony’s programmatic storytelling lies a deeper artistic mission, a reclamation of a different past. Here the history of music itself takes priority over the history of Christianity.

The notion of a “classical music” centered on a museum-like historical canon of masterpieces was novel in Mendelssohn’s time. Until the 1820s, most performances consisted of new music. No one expected a musical work to survive its composer. Against this background, Mendelssohn’s pan-historical outlook was in fact one of the most distinctive features of his artistry. He energetically championed the work of Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, and Weber alike, each of whom at times informed his own compositional language. J. S. Bach was a special case, however. Mendelssohn’s compositional training was steeped in Bach; he personally initiated the nineteenth-century Bach revival by conducting the long-forgotten St. Matthew Passion in 1829. And Mendelssohn’s preludes and fugues, chorale cantatas, and oratorios mount a sustained argument that Bach’s legacy was as meaningful to carry forward as was Beethoven’s.

Here lies the Reformation Symphony’s bravest move.

The work manifestly pays homage to Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony (1824). Like that work, Mendelssohn’s Symphony opens with a severe D-minor movement and closes with a D-major movement initiated by the joyful discovery of choral song. But where Beethoven’s finale centers on a folk-like original tune, Mendelssohn offers a famous chorale whose successive appearances clearly evoke Bach’s variegated handling of such congregational songs. Mendelssohn does not replicate Bach’s language, but reimagines it spoken with a Romantic inflection. Mendelssohn seeks, in short, to carry forward the weightiest of modern musical genres, the symphony, by carrying it backward, bringing Bach’s paradigm of musical greatness into conversation with Beethoven’s.

The Reformation Symphony is about Luther’s epoch-making work, but it is also about musical canon formation. Indeed, Mendelssohn’s memorialization of Protestantism’s early sixteenth-century founder probably speaks less forcefully today than his inventive reclamation of a giant of early eighteenth-century Protestant music in Beethoven’s symphonic world.

You can hear conductor Marie Jacquot and the Aspen Chamber Symphony perform Mendelssohn’s Symphony no. 5, “Reformation,” on Saturday, July 5 at 5:30 pm in the Klein Music Tent.

Peter Mercer-Taylor, Professor of Musicology at the University of Minnesota, is author of The Life of Mendelssohn (Cambridge University Press, 2000) and editor of The Cambridge Companion to Mendelssohn (2004). His other writings on Mendelssohn include articles in The Journal of Musicology, 19th-Century Music, and numerous edited volumes. Mercer-Taylor’s latest book, Gems of Exquisite Beauty: How Hymnody Carried Classical Music to America (Oxford University Press, 2020), explores nineteenth-century American hymnody’s strange fascination with European classical music. Its NEH-funded website, AmericanClassicalHymns.com, includes forty-four hymn tunes culled from Mendelssohn’s work. Mercer-Taylor is President of the Society for Christian Scholarship in Music.<br>test

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03