-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

The Lifelong Suffering of a Genius: Beethoven’s Personal Struggle

Friday, July 23, 2021

Posted By:Nancy Swift Furlotti, Ph.D.

—

We often hear about early trauma and its impact psychologically. We see not only how a child responds to his or her early environment but also the history of trauma passed down from one generation to another—patterns of behavior that may include social factors as well as the family’s ability to cope with life’s difficulties. While many are able to successfully counter the devastating effects of trauma through regular counseling and other professional resources, for others, it can remain a continual struggle. In Ludwig van Beethoven’s case, his very harsh beginning continued to impact his sense of self and personal relationships for his entire life.

From a very early age, Beethoven’s father pushed him to follow in the footsteps of Mozart, to become the music world’s next child prodigy. The young Beethoven was forced to play at all hours of the day and night. One story tells of his drunken father returning from a bar late at night with friends and forcing little Ludwig to get up and perform on the pianoforte for their entertainment. Standing on a stool to reach the keys, he was beaten for every missed note, torture that went on throughout the night. This episode alone gives important clues as to how his personality was being shaped. The poor child could not trust his father, creating a state of fear and anxiety. By nature, parents mirror behaviors for their children, so Beethoven learned these negative behaviors from a young age, which increasingly appeared as he grew older.

Beethoven did have a loving relationship with his mother, whom he described as his best friend, but she died when he was only sixteen years old. At that point Beethoven had to become the “parentified child” and take care of his two younger siblings, which he did with both love and harsh judgement, similar to his father. One particular episode from later in life illustrates the darker side of this behavior. When his brother (Caspar Carl) died in 1815, Beethoven was initially named the sole guardian of his nine-year-old nephew, Karl. However, a last minute change made Karl’s mother co-guardian, whom Beethoven immensely disliked. What ensued was an ugly, four-and-a-half year battle over possession of the boy. Beethoven was ultimately granted full guardianship, but at great cost. He was overbearing, harsh, and occasionally violent towards his nephew, and Karl would frequently escape to his mother’s house in response, much to Beethoven’s disapproval. A devastating blow came several years later—in August 1826, Karl attempted suicide. Though the boy lived, Beethoven was devastated by this and granted his nephew’s wish to join the army.

Alcoholism was also a major issue in the Beethoven family—his grandfather, his father, and Ludwig himself were all alcoholics. Continual dependence on alcohol often results in erratic, unpredictable, and at times, aggressive behavior. There are numerous instances of these traits throughout Beethoven’s life, one of the most infamous being his 1806 tirade to his patron, Prince Karl von Lichnowsky, in which the composer declared, “Prince, what you are you are by accident of birth; what I am I am through myself. There have been and still will be thousands of princes; there is only one Beethoven.” Because of problems with intimacy, alcoholics tend to have increased anxiety that results in dark, unapproachable moods. Beethoven had a well-earned reputation for being highly disagreeable.

This didn’t stop him from completing an enormous body of work. In the summer and fall of 1802 (one of the most personally turbulent periods of his life), for example, he completed a remarkable set of compositions in the idyllic surroundings of Heiligenstadt, all while coming to terms with his encroaching deafness. (This included the Second Symphony, the Opus 33 bagatelles, the three Opus 30 violin sonatas, and the first two Opus 31 piano sonatas.)

Early trauma frequently results in the individual escaping into an inner world of his own making that can be a safe harbor from the perilousness of the outer world. It can be a place of creativity where ideals of freedom and perfection can take hold. This is where Beethoven’s genius prevailed. Yet, as he set himself up to aspire for greatness and beauty, nothing less was acceptable. This ideal was projected onto the women he fell in love with, none of whom could ultimately live up to his ideal. He so longed for love and companionship but was incapable of compromise. This resulted in depression, feelings of despair, unrelenting self-criticism, and somatic disturbances such as the gastrointestinal illness that he later attributed to his social isolation. His deafness certainly did not help but instead pushed him further into his own inner world. In this place of mind with the acute colors of his torment, loneliness and idealization, he let his creative genius flourish, touching the transcendent and the heart of our being as we listen to his exquisite creations.

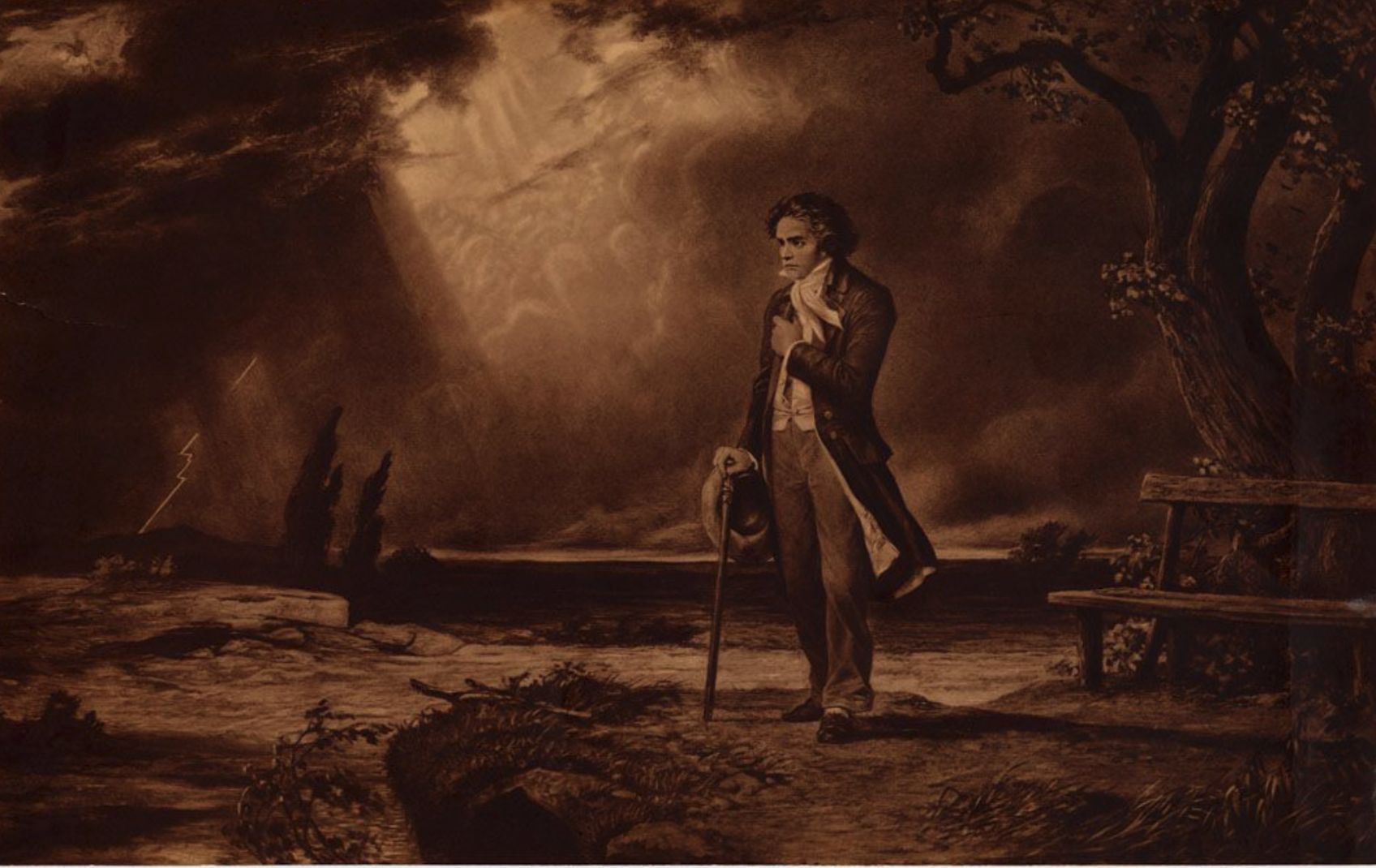

- Image: Beethoven in the Storm, c. nineteenth century (lithograph) after a painting by Karl Schweninger I. Reproduced with permission from the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University.

Nancy Swift Furlotti, Ph.D. is a Jungian Analyst in Aspen, Colorado. She is a past president of both the C.G. Jung Institute of Los Angeles, where she trained, and the Philemon Foundation, which published C.G. Jung’s Red Book. She is on the boards of the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara, the Smithsonian National Asian Museum, and the Aspen Music Festival and School. She has written numerous articles, co-edited a number of books, and lectures internationally on Jungian topics such as dreams, mythology, trauma, and the environment.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03